Yesterday Margaret and I took her parents to visit a historical museum in the town of Millicent, 50kms from here.

Part of the display is dedicated to ship-wrecks, a frequent part of life along the coastline of our region.

The photo below shows a map with tags of the wrecks that took place between 1838 and 1938. There are about 50. Displayed alongside of it is a similar map showing wrecks that took place along the coastline heading north-west to Adelaide. There were a similar number of tags on that map.

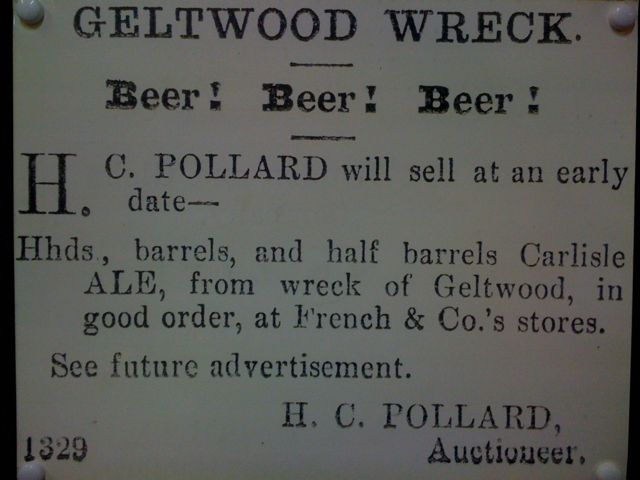

In the midst of these frequent tragedies life went on. This photo shows an advertisement selling kegs of beer recovered from one vessel.

These memorials point to a past age, one in which life was very different to the way it is now.

It is not just our lifestyles which have changed, though. Our values have altered to such an extent that we can scarcely identify with the morality and standards of our forebears.

When the Gospel was shared with past generations, concepts of obedience and sacrifice at least resonated with the personal experiences of the hearers. This is much less the case when communicating to a generation ingrained with the concepts of self-fulfillment and subjectivity.

Don Carson refers to the difficulty that James Cameron had portraying the evacuation of the Titanic when making the film of that name. Values had changed so much that history was rewritten to fit our expectations. I read this last week in Carson’s new book, Scandalous. Kevin DeYoung put the text in his blog, so it saves me the trouble of scanning or typing.

Perhaps part of our slowness to come to grips with this truth lies in the way the notion of moral imperative has dissipated in much recent Western thought. Did you see the film Titanic that was screened about a dozen years ago? The great ship is full of the richest people in the world, and , according to the film, as the ship sinks, the rich men start to scramble for the few an inadequate lifeboats, shoving aside the women and children in their desperate desire to live. British sailors draw handguns and fire into the air, crying “Stand back! Stand back! Women and children first!” In reality, of course, nothing like that happened. The universal testimony of the witnesses who survived the disaster is that the men hung back and urged the women and children into the lifeboats. John Jacob Astor was there, at the time the richest man on earth, the Bill Gates of 1912. He dragged his wife to a boat, shoved her on, and stepped back. Someone urged him to get in, too. He refused: the boats are too few, and must be for the women and children first. He stepped back, and drowned. The philanthropist Benjamin Guggenheim was present. He was traveling with his mistress, but when he perceived that it was unlikely he would survive, he told one of his servants, “Tell my wife that Benjamin Guggenheim knows his duty” –and he hung back, and drowned. There is not a single report of some rich man displacing women and children in the mad rush for survival.

When the film was reviewed in the New York Times, the reviewer asked why the producer and director of the film had distorted history so flagrantly in this regard. The scene as they depicted it was implausible from the beginning. British sailors drawing handguns? Most British police officers do not carry handguns; British sailors certainly do not. So why this willful distortion of history? And then the reviewer answered his own question: if the producer and director had told the truth, he said, no one would have believed them.

I have seldom read a more damning indictment of the development of Western culture, especially Anglo-Saxon culture, in the last century. One hundred years ago, there remained in our culture enough residue of the Christian virtue of self-sacrifice for the sake of others, of the moral imperative that seeks the other’s good at personal expense, that Christians and non-Christians alike thought it noble, if unremarkable, to choose death for the sake of others. A mere century later, such a course is judged so unbelievable that the history has to be distorted (30-31).

Scandalous is a challenging and helpful read.

It is available from Koorong for $17.00